Driving Through the In-Between - Part 1

Here’s the thing: after driving what seems to be countless hours in the Great American Desert, you start wondering at what exact point in time you shifted into a different state of mind, into a different reality. All good road trips, after a while, become liminal. Is it because of the uncanniness of miles and miles passing repeatedly in the rearview mirror or is it because you never stop and the landscape hardly changes? The weariness takes its toll on you, for sure, nevertheless, it also enables you to perceive the richness of this alternative reality.

I have taken two road trips in California: the first one was happy, innocent, infused with childlike wonder, the second was darker, more stressful and more lonely.

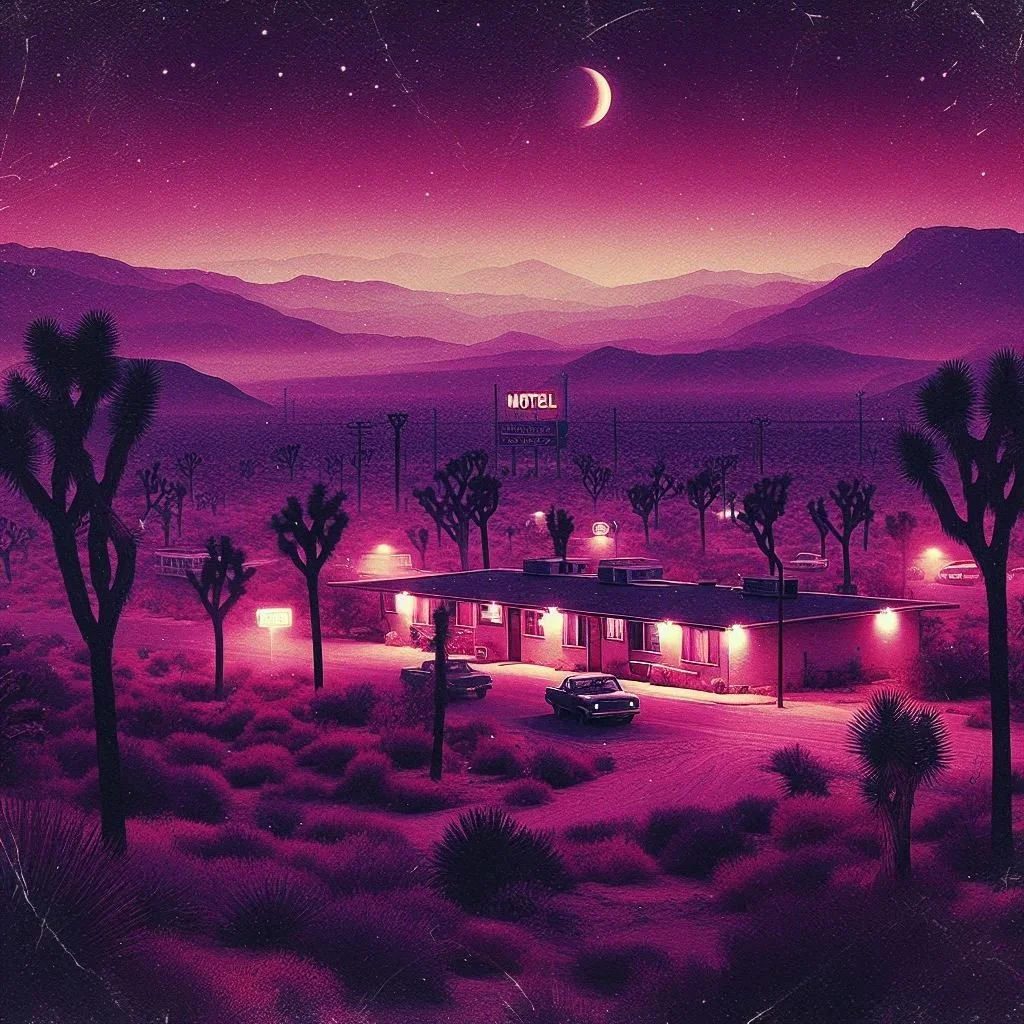

The first one let me have the big gulp of California: I drove around the Golden State from Los Angeles to San Francisco, from Yosemite to Monterrey, checked Road 66 to PCH, with occasional visits to Nevada and Arizona, from Las Vegas to Grand Canyon. The second was from Los Angeles to Palm Springs, from Joshua Tree to Sequoia National Park, off-season, desert-stuck, less interactive, more contemplative. Both have taught me something different about myself and about the way I thought about road trips. When you read Kerouac’s On the Road, I am sure there is a contrasting image of what a road trip is: often dreamlike, idolized images of beautiful sceneries and never-ending roads. Let me quickly underline I am talking about the Great American Road Trip in the Great American Desert. On this second road trip, I understood the harsh beauty of a road trip and I deep dived into this beauty many times. Imagine the following: thanks to the jet lag, I spent hours at dawn by the window of my motel room, looking at the lower peaks of Queen Mountain in San Bernardino County, the palm trees on 29 Palms Highway only lit up by that one or two trucks that have some cargo to deliver. In my ears Matthew Halsall’s “I’ve Been Here Before”, which adds another layer to the whole concept of liminality. The night is never fully dark, it is dark purple, cinematic, eerily silent. If you step outside, and go down to the parking lot, there is a dim light from the washing room, and there is the faint buzz of a snack machine. And you go wondering: “Where did I see all of this?” In movies, reels or photos, because this is a stereotypical motel ambience. I choose to experience my road trip stereotypically: “What is your signature dish?” I often asked to waiters and waitresses, and I found solace in roadside ribs and cactus omelettes with my American coffee - which never tastes as bad as they say.

Like I said all good road trips became liminal at some point: I do mean it, as this is the point when your mind starts accepting this difference between where you came from and where you are heading to. This transition is what should happen, and, this is often supported by the seemingly endless lines of motel rooms, roadside diners and sights you have planned to see. Nothing is static on a road trip, of course. One hour of driving next to orange orchards, then six more hours driving just to arrive at a ghost town was the recipe for getting into this liminality. Following Victor Turner’s concept, I have always been obsessed with the idea of being in a transitional space: airports or motels, the feeling of the slightly uneasiness of being in a space that is unknown and unhomely, that’s what I needed. Because liminality indicates that you haven’t arrived to your destination, you are still doing this trip. In my case, one of my destinations was the desert, an ultimate no-man’s land, the in-between. Having found how people live in this breathtakingly barren, yet gorgeous environment made me want to look for more. My car dropped me off at Skull Rock, which is a rock formation that resembles a skull of an extraterrestrial entity that had lived before the first human being stepped into existence. It could also well be that they were living with us as well. None of these matter as these are my speculations only, it has no significance in describing this natural beauty in Joshua Tree National Park. What matters is that being in Joshua Tree National Park feels like stepping into a huge biome, that copies and pastes its very own specific and natural patterns. From Joshua trees to rocks and sandy patches with cacti, you will see rabbits, and lizards basking in the Sun, or run away from a presumed danger. Every stop is shielded with “Don’t Die Today” signs, to which I did not pay attention until I got my first heatstroke upon climbing Ryan Mountain. The harsh truth was I could see nobody on my horizon, and the Sun at noon was not going to go anywhere, so I needed to find a rock that cast some shadow over my head. My water was scarce and I was halfway from the top that would later show me the sight over the park from 5456 feet. It is a strenuous walk, and I had already been to the desert for 3 days on and off. Under the scorching Sun I was wondering if liminality has a specific time and weather? On rare occasions, I believe, you can catch the liminal experience at work when it is sunny: just like some of Edward Hopper’s paintings, but more often than not, I would put its true form between dusk and dawn. That is why I went for stargazing alone in Joshua Tree National Park before dusk: I knew I had to drive a bit further to reach some good spots, so with the Sun setting, I started driving into the endless desert. There is something sublime when you drive in the desert at dusk: the purple-blue horizons enhance the loneliness, and the spring wind is cool enough to counterbalance the daytime heat. My radio decided to rebel against stereotypes: instead of blasting Willie Nelson, or Bob Dylan, my soundtrack is the Father of Ethio-Jazz, Mulatu Astatke’s “Tezeta”. The mellow, repetitive guitar and saxophone proved to be the perfect choice for my lone drive there. Upon arriving, it was already dark. My plan is to see and capture the Lyrid meteor shower that can peak at 15-20 meteors per hour. I chose a parking lot alongside with some other travelers and families. They are loud, and sometimes do not respect the stargazer’s etiquette of keeping it dark and silent. I don’t mind, I am focusing on the night sky as it soon opens up and shows galaxies and milky ways and meteors, hopefully. The first set of stars is the Orion Belt, or Las Tres Marias as I had learned recently. My surroundings, the parking lot and the bigger rocks begin to change into a strange and dark surface of a planet that I don’t know anymore. The night sky gave off some light, but masterfully keeps most of the landscape dark. I remember passing by an observatory on my way here, I wonder what the night sky would look like through the telescope. I keep looking for meteors and making some photos but I am unlucky - no meteors in sight. After some time, I go back driving into the haunting darkness. Nobody is there in front of my car or behind, just the way I intended. Now I have a little bit more than an hour to drive in this darkness, where animals can appear in front of my headlights, however, no animals were harmed. Only some other people on the roadside in total darkness, and I pray they do not decide to run into my car today. It really feels otherworldly: the immense territory of the glorious desert, where solo travelers such as myself has gone missing, died or survived, where there have been ghosts reportedly, where UFOs have been seen and where some might experience psychological disorientation by the arid silence. With every turn I am getting closer to civilization, and as the adrenaline is working in my body, I am trying to focus on the road. “What would I do if my car broke down?” Probably wait for the morning, and for the first rangers that keep passing by every now and then - I have my blanket, some cereal bars and warmish clothes, yet I am not planning to spend the night out here. Luckily, I made it out without any problems, but, a bit disheartened by the missed meteors.

Some time later I passed by the Integraton, a dome-shaped observatory near Joshua Tree that was built by George Van Tessel, an aviator and an ufologist - but it was closed. I check the calendar: it is closed on Mondays, so I get out of the car to take a look at the observatory. Needless to say, nobody is around and once again the desert loneliness is my only companion. The Integraton was originally built as a rejuvenation machine and a tool for time traveling, nowadays it is used for sound bath sessions and occasional concert venue. Acoustics are indispensable to the structural integrity of the Integraton: Van Tessel claimed to have received messages from aliens from Venus. Without using a single nail, the Integraton is built only of wood providing exceptional acoustics to the building. And there is not a single building nearby: only the vast desert - it is one of the best locations for a healing retreat or capturing signals from extraterrestrials, I guess. As I continue driving, I make a detour to Calico, one of the most haunted places in California. Considered as a ghost town, Calico was once California’s biggest silver mining town with over 500 mines. Before being abandoned entirely in 1907, it produced 20 million USD in silver. After some decades later, Walter Knott - an entrepreneur and the founder of the amusement park “Knott’s Berry Farm”, bought several ghost towns, including Calico and revived the town by rebuilding it in its former “wild west glory”. Upon my arrival, Calico was everything, but a ghost town: shops and tourists are everywhere, a train ride is available on some of its scenic canyons - where there is supposed to be a specter of a vanished miner woman. The dusty main street and the dustier side streets behind the row of shops and houses, do give off the wild western atmosphere, yet, I leave soon because I still have to arrive to my next destination - the mighty and gigantic land of Sequoia.